SCIF Inept UR #3: IMR Offers No Hope for Injured Worker

In California workers’ comp, the insurer has the final say over an injured worker's medical care.

So what if the insurer gets it wrong? What if the insurer denies appropriate and medically necessary treatment through miserliness, incompetence, or both? What’s an injured worker to do?

In theory, California offers recourse: Independent Medical Review (IMR), through which an injured worker can appeal the insurer’s Utilization Review (UR) decision. The only problem? IMR is impossible for injured workers to navigate, riddled with convenient loopholes for insurers, and wildly unlikely to succeed.

A 2022 report from the Division of Workers’ Compensation (DWC) found that injured workers who filed for IMR to dispute a treatment denial by the insurer’s Utilization Review Organization (URO) in 2021 lost 91% of the time. This means that in 2021, IMR determined that 91% of the disputed treatment recommended by physicians was medically unnecessary.

Ask yourself, Californians — how credible is it that 91% of the time, a distant URO hired by an insurer is more accurate in its medical judgment than the physician caring for the injured worker? Remember, these URO organizations:

- Never examine the injured workers, and

- Make their medical decisions by reviewing (sometimes incomplete) medical records sent to the URO by the insurer

That staggering 91% statistic begins to make more sense when you read stories like the one below, which illustrates just how Sisyphean a task it is for an injured worker to prevail through IMR, and how laughably easy it is for an insurer like State Compensation Insurance Fund (SCIF) to operate in a system seemingly built to protect its financial interests over the health of injured workers.

SCIF Denies Treatment for “Missing” Documentation (That Isn’t Missing)

As detailed in this post, an injured worker with head trauma required continued therapy to restore normal cognitive function. But SCIF’s URO, EK Health, issued a UR decision denying the therapy.

EK Health claimed that the treatment denial was due to a lack of medical records establishing the therapy’s goals, progress thus far, and anticipated future timelines. However, the doctor had included with the RFA a detailed, comprehensive 9-page medical report, which included the exact information EK Health claimed was missing.

Per California law, the treatment denial will stand for an entire year unless the injured worker prevails through IMR — of which there is a roughly 9% chance of success, according to DWC statistics.

Per IMR regulations established by the DWC, only the injured worker (not the doctor) can file for IMR. Accordingly, this injured worker with damaged cognitive function is expected to navigate the mind-melting bureaucratic labyrinth of IMR and advocate for themselves. And the proverbial deck is stacked against them, as we demonstrate below.

IMR Eligibility Rules Guarantee Insurers Win

Upon denying or modifying medical care, California Labor Code Section 4610.5. dictates that the insurer must send the injured worker an IMR form completed by the insurer so the injured worker can file for IMR.

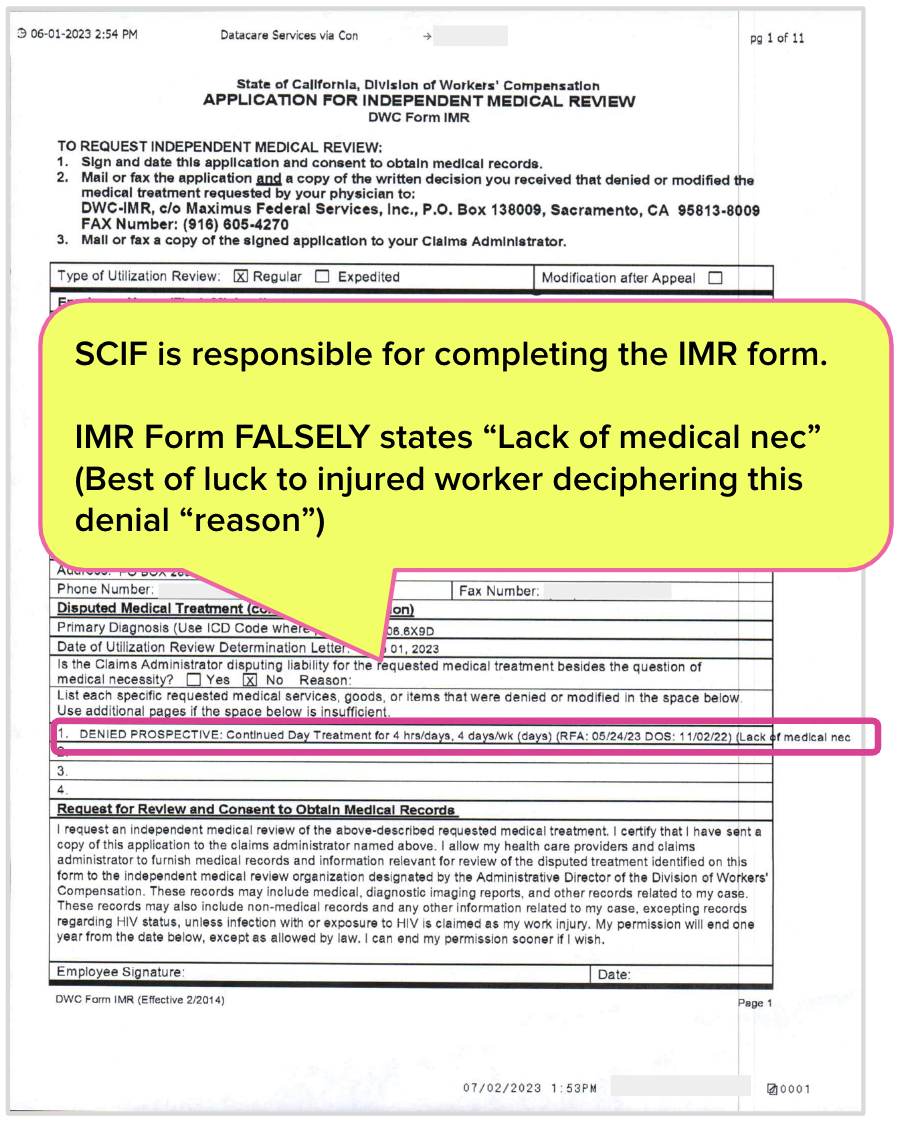

Below is the IMR form SCIF completed and sent to the injured worker, which states (emphasis added):

DENIED PROSPECTIVE: Continued Day Treatment for 4hrs/days, 4 days/wk (days) (RFA:5/24/23 DOS: 11/02/22) (Lack of medical nec

The operative phrase SCIF included when completing the IMR form on behalf of the injured worker is “Lack of medical nec” (which we assume is shorthand for “lack of medical necessity”).

According to DWC rules, an authorization dispute is deemed ineligible for IMR if the UR decision “does not reflect a determination of medical necessity (conditional non-certification).” As further explanation, the DWC defines a “conditionally non-certified decision (CNC)” as follows:

“A UR decision that has been denied because the treating physician has not provided the medical information requested by the claims administrator that is required to make a medical necessity determination on the treatment recommendation.”

In other words, SCIF, when completing the IMR form, appears to allege that the physician did not provide the medical information necessary to make a medical determination, as reflected in SCIF’s UR decision.

(Of course, the physician submitted the information to SCIF with the RFA, as recorded and time stamped by daisyAuth. SCIF’s claim of “lack of medical nec” is demonstrably false.)

Conveniently for SCIF, the DWC has devised an RFA system that allows insurers to:

- Complete the IMR form on behalf of the injured worker

- Assert non-receipt of essential medical documentation

- Circumvent IMR by claiming missing medical information

Despite SCIF and EK Health’s abject failure to conduct UR properly, the allegedly-but-not-actually missing medical records would likely render this dispute ineligible for IMR. And yet, somehow, the DWC can still believe it’s plausible for treating doctors to be correct only about 9% of the time.

We can’t make IMR easier for injured workers. But we can make authorization easier for doctors, with daisyAuth RFA technology — request a demo below.

REQUEST DEMO

DaisyBill provides content as an insightful service to its readers and clients. It does not offer legal advice and cannot guarantee the accuracy or suitability of its content for a particular purpose.

.gif)

.gif)