CA DWC: Claims Administrators' IBR Wingman

In California, claims administrators can expect little or no repercussions for failing to comply with workers’ comp payment laws and regulations.

Meanwhile, the Division of Workers’ Compensation (DWC) will intervene to ensure consequences for even the slightest error made by providers in the billing or appeals process.

Case in point: a Qualified Medical Evaluator (QME) recently billed Contra Costa County Schools Insurance Group (CCCSIG) for a Comprehensive Medical-Legal Evaluation. Unfortunately, the provider erroneously failed to include an important billing code modifier, which resulted in a significantly reduced payment.

Per California requirements, the evaluator sent CCCSIG a Second Review appeal explaining the error and requesting the additional funds due. But rather than addressing the issue raised in the appeal, CCCSIG incorrectly (and non-compliantly) denied the appeal, declaring it a “duplicate” of the original bill or “balance forward billing.”

After the incorrect appeal denial, the QME’s only remaining option under California law was to pay $180 and request Independent Bill Review (IBR). Given the relatively simple billing error and CCCSIG’s mistake in labeling the appeal as a “duplicate,” this dispute should have been an open-and-shut case.

The DWC, however, had other ideas.

Effectively acting as CCCSIG’s wingman, the DWC declared the dispute ineligible for IBR because the provider's signature was omitted from the Second Review appeal form. Ignoring CCCSIG's non-compliance in denying the appeal, the DWC allowed CCCSIG to retain thousands of dollars in reimbursement owed to the QME.

This would be less frustrating if the DWC ever applied such stringent compliance standards to claims administrators, whose blatant contraventions of laws, regulations, and rules—to say nothing of minor administrative requirements—are treated as a matter of course.

In this case, the provider made trivial errors, which are inevitable in any administrative system. In contrast, CCCSIG’s error misidentified an appeal as a duplicate bill, costing the provider $2,015. Yet the DWC punished only the provider’s mistake, enriching CCCSIG in the process.

Provider Billing Errors: Unforgivable

California’s Medical-Legal Fee Schedule (MLFS) establishes reimbursement rates for Medical-Legal services with primary billing codes, along with modifiers that may increase the rates paid for each primary billing code.

The QME conducted a Comprehensive Medical-Legal Evaluation, billable with code ML201. However, psychiatric issues were the focus of this particular evaluation, and the QME is a psychiatrist. This allowed the QME to apply Modifier 96, which doubles the reimbursement rate.

Unfortunately, the provider’s office accidentally omitted Modifier 96. As a result, CCCSIG—quite understandably—reimbursed the evaluator at the rate for a standard, non-psychiatric evaluation.

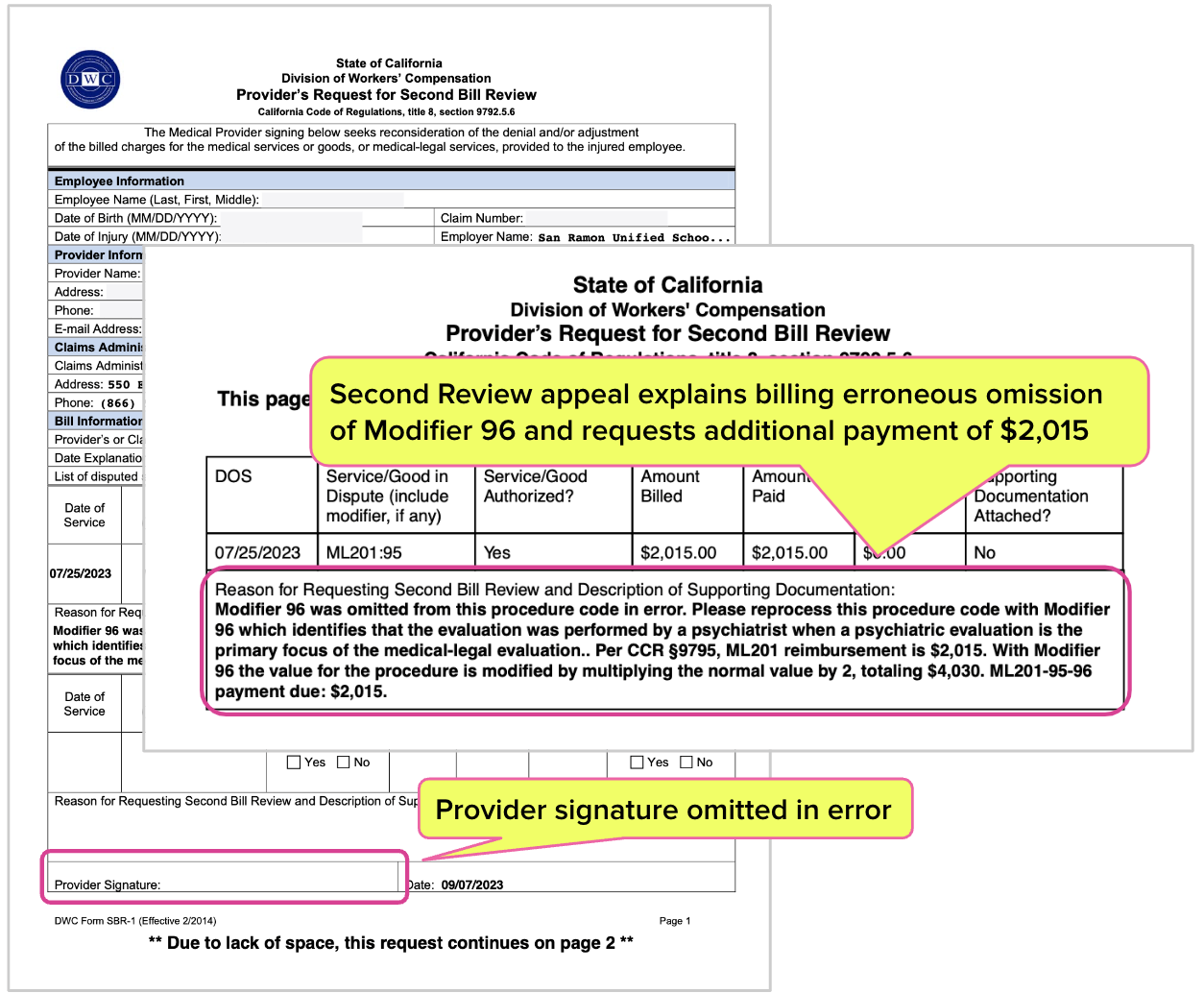

The provider sent CCCSIG the required Second Review appeal form (the SBR-1, shown below) to remedy the error, explaining that Modifier 96 applied to the bill and requesting the additional $2,015 owed per the MLFS.

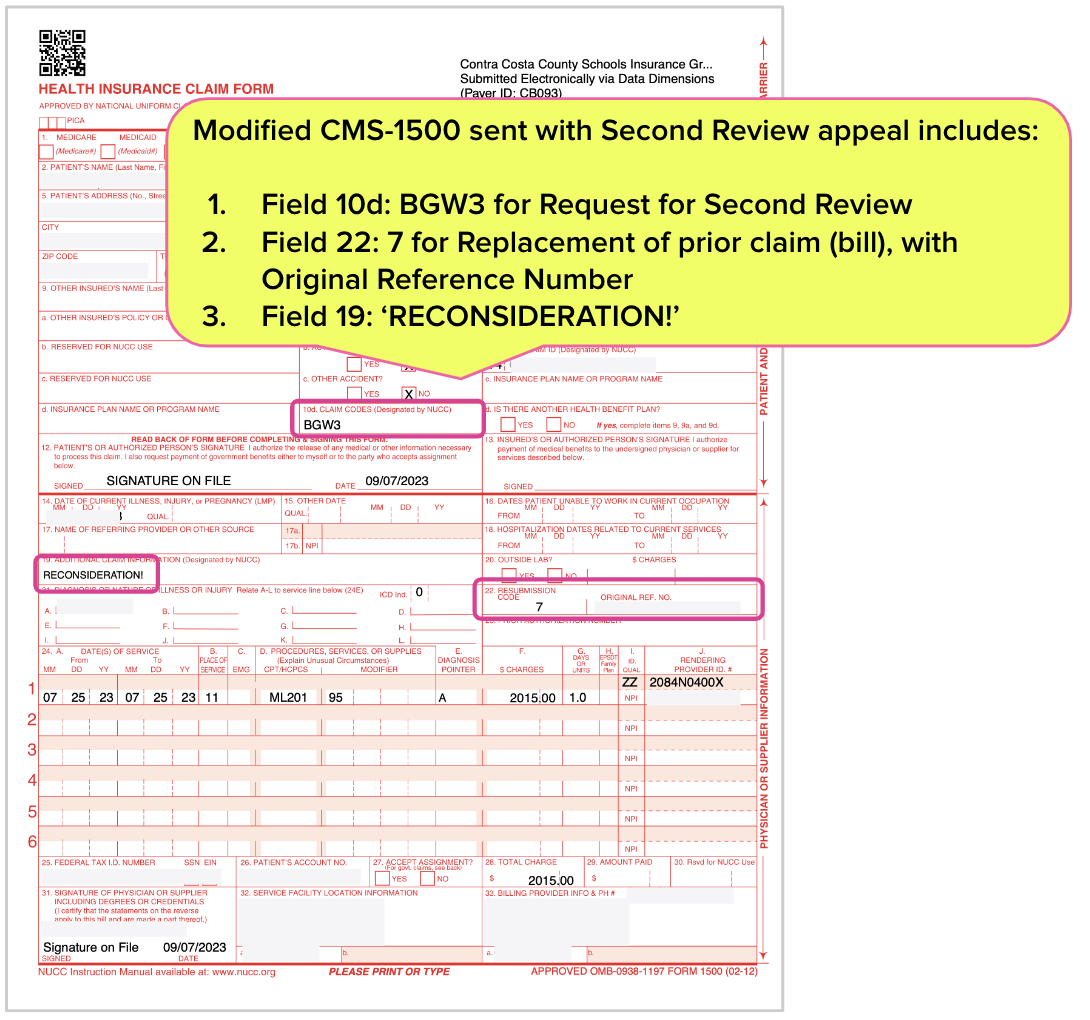

Per DWC instructions, the appeal also included the standard CMS-1500 billing form with unmistakable indicators of a Second Review appeal, as opposed to a duplicate of an original bill:

- ‘BGW3’ in Field 10d

- ‘7’ in Field 22

For good measure, ‘RECONSIDERATION!’ was entered in Field 19 for “Additional Information,” leaving no reasonable doubt that the submission was an appeal.

The documentation submitted with the appeal included the Explanation of Review (EOR) that CCCSIG sent with the original payment, and the Medical-Legal report demonstrating that the evaluation was psychiatric.

Unfortunately, the SBR-1 form was missing the provider’s signature—a fact that CCCSIG would not object to, but that the DWC would use to prevent this QME from receiving appropriate payment.

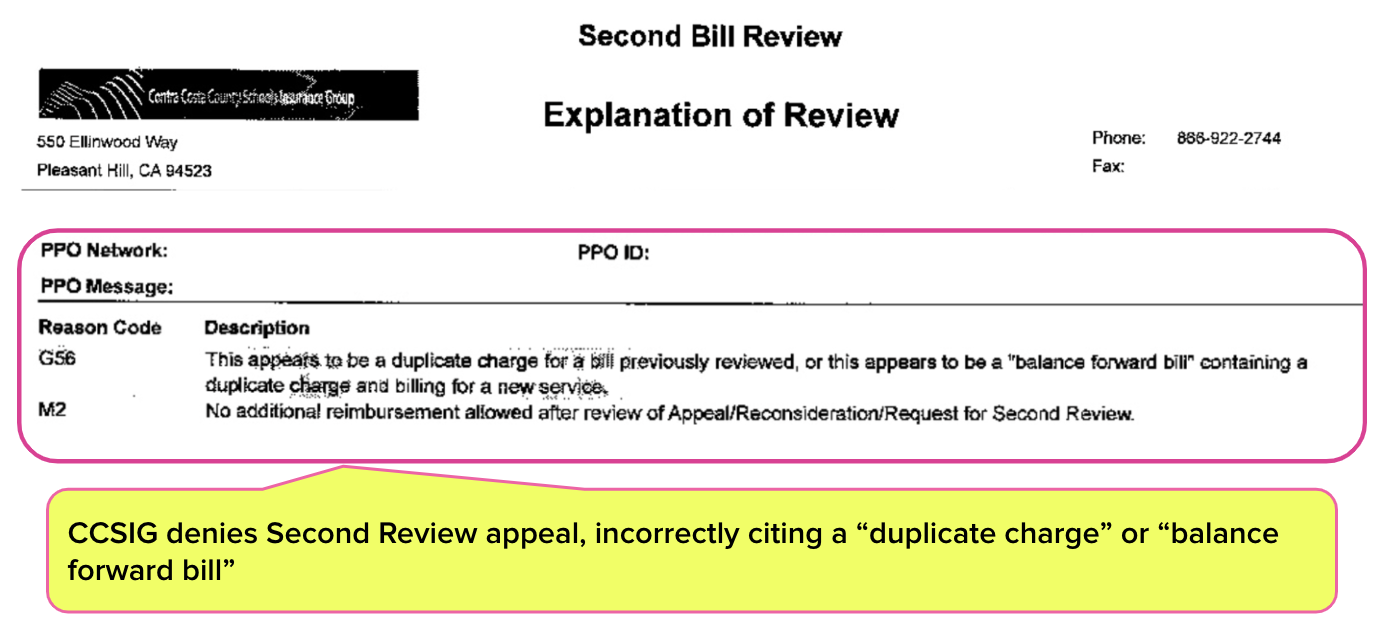

CCCSIG denied the appeal without addressing the QME’s billing error or the missing signature. Instead, the final EOR incorrectly stated:

“This appears to be a duplicate charge for a bill previously reviewed, or appears to be a “balance forward bill” containing a duplicate charge and billing for a new service.”

DWC Kills IBR on Technicality

When a claims administrator incorrectly denies payment following a Second Review appeal, the provider's only recourse is to request IBR by Maximus, a private entity that conducts IBR on the DWC’s behalf. But before Maximus takes a case, the DWC may determine whether or not the dispute is eligible for IBR.

Valid reasons for a DWC “ineligible” ruling include questions about liability or authorization, since IBR was designed strictly to settle disputes over the amount of reimbursement owed. In other words, the DWC tries to ensure that Maximus doesn’t have to deal with complex cases involving “threshold” issues that bill review cannot address.

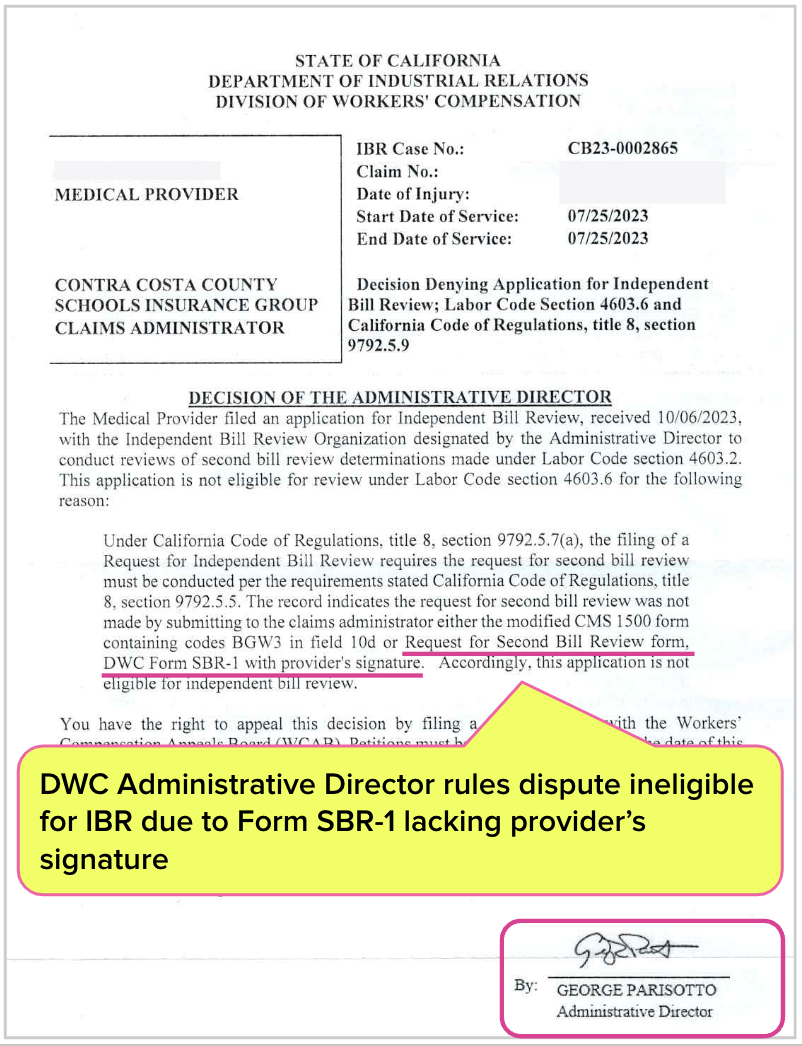

Yet, in this case, the DWC ruled the dispute ineligible for IBR because…the SBR-1 form the provider sent to CCCSIG lacked the QME’s signature.

The DWC took it upon themselves to adjudicate the Second Review appeal (rather than the bill itself) to the benefit of CCCSIG—while simultaneously ignoring CCCSIG’s non-compliant denial of the appeal based on the verifiably untrue notion that the appeal was a “duplicate charge” or “balance forward bill.”

This dispute began with a missing billing code modifier, a straightforward matter of bill review. By deeming this dispute ineligible for IBR based on a trifling technicality, the DWC seems to have gone out of its way to ensure that this QME forfeited 2,015 of their hard-earned dollars.

Meanwhile, the very same DWC allows CCCSIG and (other claims administrators like Sedgwick) to trample state laws and regulations without consequence, doing more damage to the workers’ comp system than any number of missing signatures.

Below is the “Decision Denying Application for Independent Bill Review” rejecting the IBR request, complete with DWC Administrative Director George Parisotto’s signature.

DWC Polices Providers, Coddles Claims Admins

Imagine if every time a claims administrator erroneously denied a Second Review appeal as a “duplicate” bill, or failed to respond by the mandated deadline, or furnished a plainly untrue “threshold” issue to preclude IBR, the state automatically required the claims administrator to pay the amount in dispute.

Imagine if untimely payment, or failure to remit electronic Explanations of Review, or any of the countless violations by claims administrators (even well-established patterns of non-compliance) carried automatic penalties that the DWC enforced.

Undoubtedly, such a system would lead to a steep decrease in claims administrator errors. But in reality, such errors are profitable—and the DWC effectively stands guard over those profits.

The deck is stacked against providers, but our software and expertise helps even the odds. Reach out to learn how daisyBill can help your practice.

CONTACT US

DaisyBill provides content as an insightful service to its readers and clients. It does not offer legal advice and cannot guarantee the accuracy or suitability of its content for a particular purpose.

While this is unfortunate, and unfair, there is a remedy provided by law: The QME can appeal the decision (within the appropriate time frame) and file a DOR to get on calendar. At that point, the QME can resolve the issue or reimbursement with the whomever represents defendants. Use this: Petition for Appeal from Order of the Administrative Director pursuant to Labor Code section 4603.6 (f) and CCR section 9792.5.15 If you want to know more, reel free to reach out to me.

The elected officials of California need to hear stories like this about how the DWC, supposedly acting in the interest of the public, applies selective enforcement to its own rules and regulations, nearly always to the advantage of the insurance companies and the detriment of injured workers and the healthcare professionals who treat them. What will it take to drag a DWC official into a public inquiry session for their blatant bias and disregard for neutrality?